Above the ground: Living on a postage stamp, Eating from a thimble

This article, written by Christine Chemnitz, was published in the Soil Atlas 2015. The Soil Atlas 2015 is jointly published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, Berlin, Germany, and the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam, Germany.

The world is a big place – but we are rapidly running out of room to grow our food, and we are using it in the wrong way.

For thousands of years, humans have shaped the earth on which we live. Land is where we grow food and graze animals. It is where we build our cities and roads, dig up minerals or chop down trees. It reflects our spiritual values; it is where we go to relax.

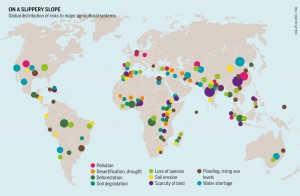

(Click to zoom) A selection of man-made problems: land scarcity and environmental damage endanger our food production. cc. Soil Atlas 2015

Land and how we use it has moulded history, politics and culture. In many Western countries, individual land ownership is associated with traditional values and social status. Lands were passed down by families from generation to generation. In socialist regimes, the nationalization of land was an expression of political power that reached a gruesome climax in the Soviet Union under Stalin, when millions were dispossessed and expelled from their farms. The structures that resulted from forced collectivization still shape the agricultural systems of much of Central and Eastern Europe.

The world has only so much land. Well into the 20th century, countries expanded their boundaries through war and colonial suppression. However, increasing liberalization and globalization of agricultural trade since the 1980s, have blurred the importance of a limited national territory. The era of the agricultural multinational firm has arrived. With branches around the globe and logistics that can handle millions of tonnes, the Big Four – Bunge, Cargill, Louis Dreyfus and ADM – shift bulk commodities from where they are grown to where they are processed and consumed. Land shortages can now be outsourced: land, the ultimate immobile resource, is now just another flexible factor of production.

The Green Revolution launched in the 1960s, ushered in the more intensive use of land in the tropics; high-yielding varieties, fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation pushed up crop yields. Fossil fuels compensated for a shortage of land. However, the limits reached by this type of non-sustainable agriculture were ignored. They came to light by the turn of the millennium, when the global ecological damage caused by industrial agriculture became evident. Now the limitation of land reveals itself again – this time from a global perspective. Demand is growing everywhere – for food, fodder and biofuels. Consumers are competing with each other. Cities and towns currently occupy only 1–2 percent of the world’s land. By 2050, they will cover 4–5 percent – an increase from 250 to 420 million hectares. Cropland has to give way; forests are being felled and grasslands ploughed up to compensate. Between 1961 and 2007, the arable surface of the world expanded by around 11 percent, or 150 million hectares. If demand for agricultural products continues to grow at the current rate, by 2050, we will need approximately an extra 320 to 850 million hectares. The lower figure corresponds to the size of India; the higher one, to the size of Brazil.

Growing demand for land heightens tensions among different groups of users. Land is an attractive investment: an increasingly scarce commodity that yields good returns. Worldwide it is the source of livelihood for more than 500 million smallholders, pastoralists and indigenous peoples. People identify with the land; for them it embodies cultural and even spiritual values. Especially in countries without social security systems, access to land is fundamental to survival. But individual and communal rights to land are increasingly under threat.

(Click to zoom) Football pitches reflect the gap between rich and poor. In a just and sustainable world, each of us would have to make do with 2,000 square metres. cc. Soil Atlas 2015

Rising demand also harms the ecosystem. A humane form of use – one that maintains the quality, diversity and fertility of a landscape – is all too rare. The more intensive the farming, the more damage it does to the environment. This is the main reason for the decline in biological diversity, above and below the ground. Every year, around 13 million hectares of forest are cleared; of the world’s primary forests, around 40 million hectares have disappeared since 2000. Fertile soils are ruined, deserts expand, and carbon that has been stored in the soil for millennia is released into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases.

Despite all these developments, the governments of developed countries still call for “green growth” – meaning replacing fossil fuels with biofuels. That is the inverse of the Green Revolution; now, intensive farming is supposed to replace petroleum. Such an intensive path towards growth disregards the goals of social justice, biodiversity and climate.

According to the United Nations Development Programme, if land use continues to increase, the world will already have reached the limits of ecologically sustainable land use by 2020. Global land use, mainly to benefit the European Union and the United States, cannot increase much more. With only 1.4 billion hectares of arable land at our disposal, each person will have to make do with just 2,000 square metres – less than one-third the size of a football pitch.

For more information please visit www.globalsoilweek.org/soilatlas-2015.